- Describe the pathophysiology of Pulmonary Hypertension (PH), and how it can be dangerous

- Who to suspect and workup for PH in the ED

- Describe the POCUS findings in PH

- Describe the management of these patients and how to avoid causing harm

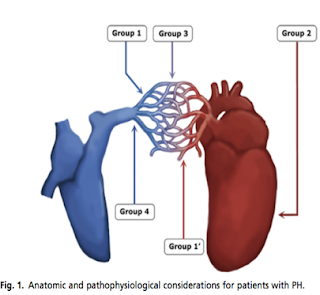

Physiology

Definition

- idiopathic

- heritable

- drug-induce

- associated with other conditions (eg. HIV, schistosomiasis, portal hypertension)

The secondary causes include:

- Group 2: Left sided heart disease (eg. valvular disease, left ventricular systolic or diastolic dysfunction)

- Group 3: Lung disease or chronic hypoxia (eg. Chronic obstructive lung disease, obstructive sleep apnea, interstitial lung disease etc.)

- Group 4: Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH)

- Group 5: Multifactorial mechanisms (eg.hematologic disorders, sarcoidosis, chronic renal failure, thyroid disorders etc) (2).

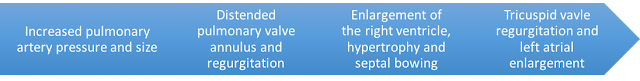

Concerning physiology

All PH groups share a common pathway of chronic RV changes:

The right coronary artery (RCA) normal supplies the RV in both diastole and systole. In PH, the increased pressure in the RV leads to filling in diastole only, thus limiting the perfusion to the hypertrophying RV (3).

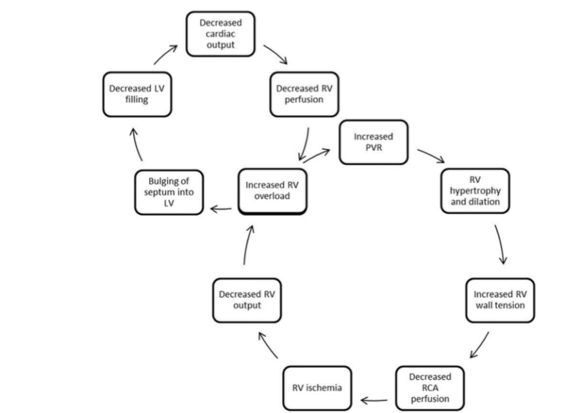

Acute RV Failure

- The RV has little physiologic reserve

- Acute illness (eg. sepsis), hyper- or hypovolemia

- Tachydysrhythmias can lead to RV failure

- Increased RV overload leads to:

- worsening LV output

- decreased RCA perfusion

- decreased RV perfusion –> leading to a “spiral of death” (4)

Who to suspect and Workup in the ED

In dyspneic patients, suspect PH if:

- Predisposing comorbidities (PH Groups 2-5)

- Physical exam:

- Normal respiratory exam.

- Loud P2, holosystolic regurgitant murmur or parasternal heave.

- Signs of right-sided heart failure (jugular venous distension, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, peripheral edema)

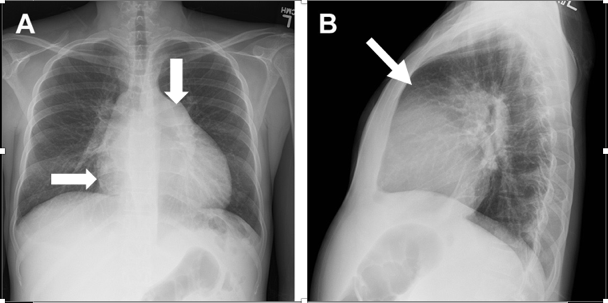

- Investigations:

- Elevated troponin

- EKG with right ventricular hypertrophy, right axis deviation, right atrial enlargement

- Chest xray with enlarged right heart border, enlarged pulmonary artery shadow, and obliteration of the retrosternal space

- CT chest can suggest PH (size of pulmonary artery >30mm, enlarged RV, pulmonary artery > proximal ascending aorta) (4; 5)

In unexplained dyspnea with a normal CT PA, what proportion of patients have PH?

An independent, prospective validation of a clinical decision rule in patients with dyspnea by Russell et al. 2015 demonstrated that patients with ongoing dyspnea and a negative CTPA had a high rate (33%) of RV dysfunction and RV overload. While the study had inherent workup and selection bias, there appears to be a high prevalence of RV dysfunction in this patient population and outpatient referral for echocardiogram should be considered (6).

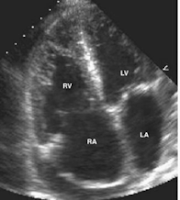

What are the POCUS findings in PH?

- RV dilatation with a RV end-diastolic/ LV end-diastolic Ratio > 0.9 on the apical 4 chamber view (4; 7)

- Flattening of the interventricular septum with a “D” Sign on the parasternal short axis (4; 5; 8)

- Thickened RV free wall >5mm on the subcostal view (8; 9)

- Other advanced findings include: right atrial enlargement, tricuspid regurgitation, TAPSE < 15mm (7; 9)

|

RV Dilation

|

Thickened RV Wall

|

“D” sign – septal bowing

|

What is the management of acute decompensated RV failure in the ED?

In a systematic review of the intensive care literature, Price et al. made the following recommendations (9):

- Optimize volume status

- Close monitoring of fluid status with a trial of diuresis or volume loading if indicated-WEAK recommendation.

- Maximize cardiac output

- Dobutamine (start 2 mcg/kg/min up to 10mc/kg/min)-WEAK recommendation.

- Milrinone (start 0.375 mcg/kg/min) –STRONG recommendation but caution given systemic hypotension is common.

- Avoid Dopamine- STRONG recommendation.

- Maintain RCA perfusion

- If needed, start norepinephrine to maintain MAP >65- WEAK recommendation.

- Add vasopressin if resistant to norepinephrine- WEAK recommendation

- Reduce Pulmonary Vascular Resistance

- Inhaled nitric oxide in select populations- WEAK recommendation

- Correct hypoxia, hypercarbia

What is the management of sepsis and septic shock in PH patients?

- Rapid treatment of underlying source as high mortality in PH patients (>48%) (10)

- Cautious volume resuscitation with 250-500 ml IV boluses at a time (11)

- Early vasopressor support with Norepinephrine +/- Vasopressin (4; 12)

- Phenylephrine NOT recommended (9)

What is the recommended method of intubation in PH Patients?

- Low quality evidence to make strong recommendations

- Induction: Etomidate or ketamine (14; 15)

- Peri-intubation: Consider NE prior to intubating to maintain MAP >65 (4)

- Post-intubation: Avoid hypotension, consider benzodiazepines or Ketamine (3; 4)

What is the management of atrial fibrillation and flutter in patients with PH?

- Sustained atrial fibrillation has a high mortality (>80% ) so CARDIOVERT if you can! (14)

- Amiodarone can be considered if cardioversion is not possible (15)

- B-adrenergic receptor antagonists or calcium channel blockers are not recommended (15)

- Digoxin can be used in COPD patients with Afib/flutter (15)

What is the management of patients on IV epoprostenol in the ED?

- Epoprostenol (Flolan) is a prostacyclin that relaxes smooth muscle in pulmonary arteries

- Improves survival of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension

- Half life of IV epoprostenol is approximately 2-5 minutes

- If Hickman blocked, start peripheral IV immediately and continue infusion of prostacyclin or patient will rapidly decompensate in RV failure leading to cardiac arrest from acutely increased RV afterload

Take Home points:

- Suspect PH in dyspneic patients and those with pre-disposing conditions

- Use POCUS to assist in diagnosis/ workup

- In acute RV failure, maximize volume status, start early inotropes and vasopressors

- Consider intubation challenges

- Cardiovert patients in atrial fibrillation/ atrial flutter

- Do not stop IV prostacyclin (eg Epoprostenol)!!

Edited and Formatted by Dr. Rob Suttie, PGY3 Emergency Medicine at the University of Ottawa

References

2. Galiè N, Simmonneau, G.The Fifth World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014, 62 (D1-D3).

3. Hoeper MM, Granton J. Intensive care unit management of patients with severe pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011 and 184:1114–24.

4. Wilcox, S., Kabrhel, C,Channick RN.Pulmonary Hypertension and Right Ventricular Failure. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2015. 66: 619 – 628.

5. Greenwood, JC., Spangler, RM. Management of Crashing Patients with Pulmonary Hypertension. Emerg Med Clin N Am 2015 and ., 33 623–643.

6. Russell, F., Moore, C., Courtney, D., Kabrhel, C., Smithline, H., Nordenholz, K., Richman, P., O’Neil, B., Plewa, M., Beam, D., Mastouri, R. and Kline, J. (2015). Independent evaluation of a simple clinical prediction rule to identify right ventricular dysfunction in patients with shortness of breath. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 33(4), pp.542-547.

7. Voelkel N, Quaife R, Leinwand L, et al. Right ventricular function and failure. Circulation 2006 and 1883-1891, 114:.

8. Matthews JC, McLaughlin V. Acute Right Ventricular Failure in the Setting of Acute Pulmonary Embolism or Chronic Pulmonary Hypertension: A Detailed Review of the Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Current Cardiology Reviews. 2008 and doi:10.2174/157340308783565384., 4(1):49-59.

9. Price LC, Wort SJ, Finney SJ, et al. Pulmonary vascular and right ventricular dysfunction in adult critical care: current and emerging options for management: a systematic literature review. Crit Care. 2010 and 14:R169.

10. Tsapenko MV, Herasevich V, Mour GK, . Severe sepsis and septic shock in patients with pre-existing non-cardiac pulmonary hypertension: contemporary management and outcomes. Crit Care Resusc J Australas Acad Crit Care Med. 2013 and 15(2):103–109.

11. Belisha S, Kastrati A, Goda A, Popa Y. Optimal value of filling pressure in the right side of the heart in acute right ventricular infarction. Br Heart J 1990 and 98-102., 63:.

12. Gold J, Cullinane S, Chen J, Seo S, Oz MC, Oliver JA, Landry DW: Vasopressin in the treatment of milrinone-induced hypotension in severe heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2000, 85:506-508, A511.

13. Igarashi A, Sato T, Tsujino I, Ohira H, Yamada A, Watanabe T, et al. Four cases with group 3 out-of-proportion pulmonary hypertension with a favorable response to vasodilators. Respiratory medicine case reports. 2013 and 9:4–7.

14. Olsson KM, Nickel NP , Tongers J , Hoeper M.Atrial Flutter and Fibrillation in Patients with Pulmonary Hypertension. International Journal of Cardiology 2013 and 167(5):2300-2305.

15. Tongers J, Schwerdtfeger B, Klein G et al .Incidence and clinical relevance of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias in pulmonary hypertension. American Heart Journal. 2007 and 53:127–132.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks