Acute alcohol intoxication and alcoholism are two separate and unique entities that we see regularly in the emergency department. As ER physicians, our role for the acutely intoxicated patient should focus on ruling out life threatening disease and ensuring their safety for discharge.

Alcoholism, however, does predispose patients to many acute and chronic complications, in particular; Wernicke’s encephalopathy, alcoholic ketoacidosisand alcohol withdrawal.

Background

· Legal Limit = 0.08% (80mg/dL); approximate conversion to IU may be calculated by dividing by 5 (mmol/L)

· Metabolism of alcohol:

o Zero order kinetics at low concentrations (via Alcohol Dehydrogenase)

o First order kinetics at high concentrations (via MEOS)

· Average rate of elimination is 3-9mmol/hr

Acute Intoxication

· In terms of detoxification; charcoal binds alcohol, but due to rapid absorption, there is no role for acute decontamination.

· Consider alternative diagnoses, ie: alcohol induced hypoglycemia, trauma, substance withdrawal, etc.

· Incidence of vitamin deficiency is rare – no evidence for regular replacement in the acutely intoxicated patient.

· Disposition:

o No treatment is able to increase the rate of alcohol elimination.

o There are no decision tools to help determine when a patient is safe for discharge, so this is best done via physician assessment. It is important to utilize caution during assessment as our ability to estimate blood alcohol concentration on physical exam alone is very poor. EtOH level is poorly correlated to level of intoxication, and should not be used alone as a guide in clinical decision making.

Alcoholism

· Typically considered a chronic problem, however there are some useful ED screening tools, including; CAGE or AUDIT-C. ED interventions (even while brief) have been shown to reduce alcohol related injuries/complications.

Alcoholic Ketoacidosis

- Alcoholic ketoacidosis should be suspected in the settings of acute stress/illness or lack of access to alcohol. Although treatment is relatively simple, the diagnosis is often missed due to failure of consideration.

- Distinct from starvation or diabetic ketoacidosis: occurs as a result of significant malnutrition with associated alcohol consumption, resulting in significant glycogen utilization.

- Urine dip will not test positive for ketones despite severe ketosis, but they will demonstrate a high anion gap metabolic acidosis. However, serum beta-hydroxybutyrate has a high sensitivity for ketoacidosis.

- Treatment: glucose, fluids (D5W!), antiemetics, treatment of the underlying cause as well as correction of electrolyte disturbances.

Wernicke’s Encephalopathy

- Diagnosis based upon the Caine criteria, and requires the patient to have > 2 of the following: dietary deficiencies, oculomotor abnormalities, ataxia or altered level of consciousness. It is important to remember that Wernicke’s is an clinical diagnosis, and therefore investigations play a minimal role in the recognition and diagnosis of this entity.

- Thiamine is beneficial and required in doses much larger than 100mg

- There is little evidence that thiamine must be administered before glucose, and therefore if hypoglycemia is discovered, glucose administration should not be delayed.

- There is some evidence to suggest initiating a starting dose of Thiamine 500 mg IV q8h x 2 days before tapering down.

- Magnesium – required for Thiamine related kinetics, and is often low in alcoholics, replace magnesium when giving thiamine.

· Note that there is a duty to notify the Ministry of Transportation of patients with alcoholism.

Alcohol Withdrawal

- Spectrum consists of Early Withdrawal, Withdrawal Seizures, Alcoholic Hallucinosis, Delirium Tremens.

- Begins ~ 6hrs after cessation of alcohol consumption, peaks at ~24-36 hours, duration ~ 2-7 days.

- Occurs as a result of loss of GABA inhibition by alcohol + the persistence of Glutamate up-regulation.

- Early Withdrawal = symptoms of autonomic hyperactivity; tremor (postural and intentional, but not resting), sweating, tachycardia, hyperreflexia, anxiety, and nausea.

- Withdrawal Seizures:

- Occur at ~ 12-48hrs

- Typically preceded by tremor

- Typically tonic-clonic seizures

- Previous withdrawal seizure places the patient at higher risk

- Alcoholic Hallucinosis = clear cognition and hallucinations. High risk of progression to Delirium Tremens.

- Delirium Tremens = profound confusion, sympathetic overdrive and hallucinations. Mortality approaches 5-35%

Withdrawal Treatment

- Benzodiazepines; Diazepam or Lorazepam

- Symptom based approach superior to scheduled dosing

- Considerations when choosing a benzodiazepine:

|

| Benzodiazepine considerations in alcohol withdrawal |

|

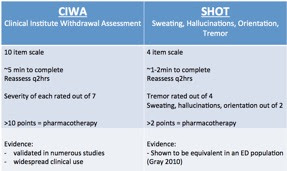

| CIWA or SHOT protocols for mild to moderate withdrawal |

- Anticonvulsants; limited evidence, no role for withdrawal treatment given potential for side effects and current safer alternative (benzodiazepines).

- Use care when considering the use of Haldol – potential to lower seizure threshold, potential to prolong QT and anticholinergic effects may worsen hyperthermia.

- Unable to use CIWA or SHOT tools for delirium tremens (due to altered mental status), however, a symptom based approach is still recommended.

- Refractory Delirium Tremens – consider barbiturates in an ICU setting.

- Other anticonvulsants have been studied extensively, however, the potential for side effects usually outweighs their benefits.

Outpatient Therapy

· Benzodiazepines are not effective for long term treatment

· If you still wish to prescribe benzodiazepines for brief symptom control, consider strategies to remove responsibility of control from the patient:

- Fax prescription to detox and write “Do not dispense remainder of meds at time of discharge”.

- Daily pharmacy dispensing.

Dr. Chris Fabian is a 5th year Emergency Medicine resident at the University of Ottawa with a special interest in Emergency Medical Services and Wilderness medicine.

Edited by Dr. Shahbaz Syed, 4th year Emergency Medicine Resident, University of Ottawa

References

1. Amato L, Minozzi S, Vecchi S, Davoli M. Benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD005063.

2. Amato L, Minozzi S, Davoli M. Efficacy and safety of pharmacological interventions for the treatment of the Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 6. Art. No.: CD008537

3. Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2006;295(17):2003-17

4. Ary, Roy D, Marlena M Wald, and Wesley Rutland-Brown, ‘Alcohol Still Kills!’, Annals of Emergency Medicine, 2002. 39;651–652

5. Association, The Canadian Medical Protective, ‘Managing Intoxicated Patients in the Emergency Department’, 2009. 1–3

6. Babor T, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders J, Monteiro MG. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. 2 ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001.

7. De Sousa A. ‘A one-year pragmatic trial of naltrexone vs disulfiram in the treatment of alcohol dependence’. Alcohol and alcoholism, 2004. 39(6):528-31

8. De Sousa A. ‘An open randomized study comparing disulfiram and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence’. Alcohol and alcoholism, 2005. 40(6):545-8

9. Duby, Jeremiah J, Andrew J Berry, Paricheh Ghayyem, Machelle D Wilson, and Christine S Cocanour, ‘Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome in Critically Ill Patients’, Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, Protocolized Versus Nonprotocolized Management, 2014. 77;938–943.

10. Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism: The CAGE questionnaire. Journal of the American Medical Association, 1984. 252(14):1905-7.

11. ‘Fitness to Drive – Ontario Medical Condition Report Form’, Ontario Ministry Of Transportation, 2009. 1–2

12. Fleming MF, Barry KL, Manwell LB, Johnson K, London R. ‘Brief physician advice for problem alcohol drinkers. A randomized controlled trial in community-based primary care practices’. JAMA, 1997. 277(13):1039-45

13. Gillman MA, Lichtigfeld F, Young T. Psychotropic analgesic nitrous oxide for alcoholic withdrawal states. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD005190.

14. Gold, Jeffrey A, Binaya Rimal, Anna Nolan, and Lewis S Nelson, ‘A Strategy of Escalating Doses of Benzodiazepines and Phenobarbital Administration Reduces the Need for Mechanical Ventilation in Delirium Tremens*’, Critical Care Medicine, 2007. 35;724–730.

15. Gray, Sara, Bjug Borgundvaag, Anita Sirvastava, Ian Randall, and Meldon Kahan, ‘Feasibility and Reliability of the SHOT: a Short Scale for Measuring Pretreatment Severity of Alcohol Withdrawal in the Emergency Department’, Academic Emergency Medicine, 2010. 17;1048–1054

16. Jackson R, Teece S. ‘Oral or Intravenous Thiamine in the Emergency Department’ Emergency Medicine Journal, 2004. 21:498-503.

17. Ipser JC, Wilson D, Akindipe TO, Sager C, Stein DJ. Pharmacotherapy for anxiety and comorbid alcohol use disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD007505.

18. Kahan M, Borgundvaag B, Midmer D et al. ‘Treatment variability and outcome differences in the emergency department management of alcohol withdrawal’. CJEM, 2005 Mar;7(2):87-92

19. Kahan M, Wilson L, Becker L. Effectiveness of physician-based interventions with problem drinkers: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152(6):851-9

20. Kahan, M. ‘Managing Alcohol Withdrawal in the ED’, CJEM 2005. 7(2);87-92

21. Kattimani, S et al. ‘Clinical Management of Alcohol Withdrawal: A Systematic Review’ Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 2013. 22(2);100-108.

22. Klimas J, Tobin H, Field CA, O’Gorman CSM, Glynn LG, Keenan E, Saunders J, Bury G, Dunne C, Cullen W. Psychosocial interventions to reduce alcohol consumption in concurrent problem alcohol and illicit drug users. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 12. Art. No.: CD009269.

23. Krishel, S et al. ‘Intravenous Vitamines for Alcoholics in the Emergency Department: a Review’ Journal of Emergency Medicine, 1998. 16(3);419-424

24. Laaksonen E, Koski-Jannes A, Salaspuro M, Ahtinen H, Alho H. A randomized, multicentre, open-label, comparative trial of disulfiram, naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence’. Alcohol and alcoholism, 2008. 43(1):53-61

25. Li, Siu Fai, Julie Jacob, Jimmy Feng, and Miriam Kulkarni, ‘Vitamin Deficiencies in Acutely Intoxicated Patients in the ED’, The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 26 (2008), 792–795

26. LN, AWS Algorithm, Final, 25 November 2015

27. Lowenfels, AB. et al. ‘Alcohol and Trauma’, Annals of Emergency Medicine, 1984. 13;1056-1060.

28. Mayo-Smith MF et al. ‘Management of Alcohol Withdrawal Delirium’ Arch Intern Med, 2004. 164:1405-1412.

29. Minozzi S, Amato L, Vecchi S, Davoli M. Anticonvulsants for alcohol withdrawal. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD005064.

30. Morgan, MY. ‘Acute Alcohol Toxicity and Withdrawal in the Emergency Room and Medical Admission Unit’ Clinical Medicine, 2015. 15(5);486-9.

31. Muzyk, Andrew J, Jonathan G Leung, Sarah Nelson, Eric R Embury, and Sharon R Jones, ‘The Role of Diazepam Loading for the Treatment of Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome in Hospitalized Patients’, The American Journal on Addictions, 2013 22(2):113–118

32. Ng SKC, Hauser WA, Brust JCM, et. al. ‘Seizures – Alcohol consumption and withdrawal in new onset seizures’ New England Journal of Medicine, 1988. 319:666-673

33. Rosman AS. Utility and evaluation of biochemical markers of alcohol consumption. Journal of substance abuse, 1992. 4(3):277-97

34. Rosner S, Leucht S, Lehert P, Soyka M. Acamprosate supports abstinence, naltrexone prevents excessive drinking: Evidence from a meta-analysis with unreported outcomes. Journal of psychopharmacology, 2008. 22(1):11-23

35. Secchi, GianPietro et. al. Wernicke’s Encephalopathy; new clinical settings and advances in diagnosis and management. Lancet Neural, 2007. 6:442-55

36. Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, Saitz R. Primary care validation of a single- question alcohol screening test. Journal of general internal medicine, 2009. 24(7):783-8.

37. Sullivan JT et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: The revised Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol scale (CIWA- Ar). British Journal of Addiction, 1989. 84:1353–1357.