LVAD Complications and Treatments

Device Malfunction

- Ensure that the controller is connected, driveline is in place and that the batteries are operational.

- One of the more common reasons for device malfunction is disconnection or battery malfunction/depletion.

- The controller will display battery life (each has a charge of about 12 hours), but if in doubt, replace the batteries, or plug the entire controller unit into a standard socket.

Pump Thrombosis

- Clot develops in the motor or fan of the device, causing pump failure.

- Patient will present in extremis with evidence of shock and hypoperfusion.

- They will have a low MAP.

- LVAD will feel hot, controller will indicate low flow and high RPM’s.

- Bedside ECHO will illustrate significant RV and LV dilatation.

- Treatment consists of Heparin (similar to PE protocol).

- Periarrest/Arresting patient – consider tPA (in close conversation with a cardiothoracic surgeon).

Diminished Cardiac Output

- Hypoxia or acidosis (ie: sepsis) will increase pulmonary vascular resistance.

- This worsens right sided cardiac output (remember – they’re preload dependent), and therefore can lead to pump failure.

- Aggressively treat systemic illness to correct hypoxia and acidosis.

- Sepsis management is as per normal guidelines (fluids, antibiotics, vasopressor support).

- If they require intubation for hypoxia; low threshold to do so. Just ensure they are preload optimized and use hemodynamically neutral induction agents (ie: ketamine).

Bleeding

- Anticoagulation: Most LVAD patients are on ASA, as well as Warfarin (INR 2-3.5).

- Pancytopenia: Mechanical sheer stress from LVAD motor results in baseline anemia and platelet lysis.

- Acquired Von Willebrand Disease: Cleavage of vWF results in an acquired pathological bleeding disorder.

- Intestinal AVM: Secondary to chronic low pulse pressure, resulting in intestinal hypoperfusion, angiodysplasia and AVM formation (typically small bowel).

- Intracerebral hemorrhage: 11% of patients with an LVAD (over a two year span), and is the leading cause of mortality in this population, other than palliation.

Treatment

- Reversal: Octaplex, Vit K, FFP to reverse the Warfarin.

- Massive transfusion protocol with 1:1:1 blood product resuscitation.

- 81% of LVAD patients had bleeding requiring pRBC transfusion over a two year span (Slaughter et al, 2009).

- Treatment of Von Willebrand Disease: DDAVP, and if your hospital has it; Humate-P (intrinsic vWF – ask your hematologists!).

- Multidisciplinary approach: Resuscitate your patient in the usual fashion: blood products, vasopressors, intubation etc. Have the appropriate services involved for source control, and ask your LVAD coordinator to turn down the flow rates (its rare that we can physically control cardiac output to control bleeding – so why not do it!).

|

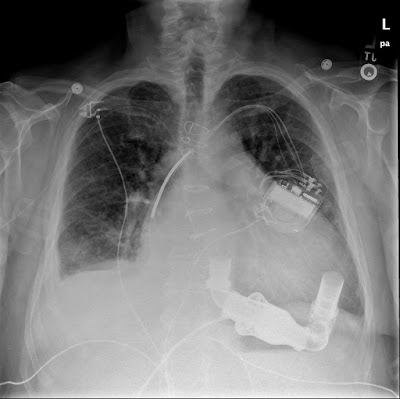

| LVAD on CXR. Image courtesy of radiopedia. |

Infection

- Most common infectious source is the is driveline; examine the surface of the skin and entrance into abdomen.

- Significant concern for intraabdominal abscess formation (given the LVAD acts as a foreign body housed within an pocket of omentum); low threshold to CT for further evaluation.

- Sepsis is common! (36% of all LVAD patients over 2 years, Slaughter et al, 2009).

- Fluids, antibiotics, hemodynamic support.

- Tend to grow MRSA, MSSA, Enterococcus and gram negatives (Pseudomonas, E.Coli ).

- Empiric antibiotics to target MRSA and also provide dual broad gram negative coverage.

Fluid Status

- LVAD’s are very preload dependent, so the hypotensive patient without signs of heart failure often requires fluid to improve cardiac output. Target a MAP between 70-90.

- Afterload reduction is important to reduce pressure off the LV/pump, to optimize MAP and perfusion if their MAP is > 100; utilize antihypertensives (ie: enalaprilat).

- Suction events are an important consideration, typically occurring in the setting of hypovolemia:

- Large negative pressures are generated by the LVAD, causing the LV to collapse upon itself and allowing leftward deviation of the interventricular septum – thereby impeding cardiac output.

- Suction events usually occur secondary to hypovolemia, but may be caused by arrhythmia, RV failure, cardiac tamponade or cannula malposition. Ultimately, initial treatment is typically fluid resuscitation and rule-out of the other causes.

Arrhythmia

- Adequate RV function is critical for cardiac output because of LVAD preload dependence.

- Therefore, these patients may not tolerate many arrhythmia’s well, as they rely on their ventricular output and atrial kick.

- Obtain an early ECG; and it should effectively be normal! Evaluate for rhythm disturbances and ischemia (especially right sided MI). If appropriate ST elevations are present the patient should be treated as a STEMI, as they may rapidly deteriorate otherwise.

- First line treatment for arrhythmia is rhythm control, in the form of electrical cardioversion/defibrillation.

- Pads should be placed in AP fashion (as to not shock over the pump.

- Beta-blockers and Amiodarone are considered the most appropriate chemical agents if required.

- Ultimately, remember that arrhythmia is a symptom of disease; so rule out the underlying cause!

- ie: Hyperkalemia secondary to hemolysis, suction events, etc.

Stroke

- Significant risk, despite anticoagulation. 19% of LVAD patients over two years developed ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke (Slaughter et al, 2009).

- Management is the same – workup and assess signs/symptoms of CVA.

- These patients are not tPA candidates for stroke.

- Similarly to regular stroke patients; target hypertension control, aiming for a MAP of 70-90, excessive hypertension requires aggressive reduction with nitrates, ace inhibitors or Labetolol.

Cardiac Arrest

- Previously there was concern that CPR would result in LVAD cannula displacement through the ventricle.

- Two limited studies looking at this (retrospective and observational with a total of 18 patients) demonstrated no instances of LVAD dislodgement.

- No brainer for me: if your patient arrests, perform CPR.

- There is an argument for a ‘chemical code’ in the literature – if your patient has a VF or VT arrest, there are successful case reports of resuscitation with defibrillation, epinephrine and atropine only as per ACLS without chest compressions.

ED Approach

1. Look

Assess your patient’s level of consciousness and perfusion status. ABC’s!

2. Listen

Listen to the precordium to assess for the hum of the LVAD motor, ensure that it is functional.

3. Measure

Check the patient’s MAP:

- Insertion of an arterial line (non-pulsatile flow gives you one number, that is your MAP).

- Manual blood pressure assessment with doppler (EDECMO for details on how to perform this).

4. Feel

Place your hand over the LVAD and controller to assess the temperature, if it is hot – consider pump malfunction! Follow your driveline to the controller, examine the pump settings in regards to RPM, power and flow.

5. Manage

- Rule out device failure or complications

- Source control and reversal of bleeding

- Broad spectrum antibiotics for infection

- Management of shock

- Preload and afterload optimization (target MAP 70-90)

- Treatment of arrhythmia’s

- Remember that they’re prone to a host of medical complications, don’t become overwhelmed by the LVAD !

- Involve your LVAD team and coordinator!

- If the patient arrests – perform CPR.

References