- Provide an overview and assessment of the most popular chest pain risk scores in the ED

- Evaluate the effectiveness of clinical gestalt for the assessment of chest pain ED

- Discuss the medical legal implications surround the utilization and documentation of chest pain scores.

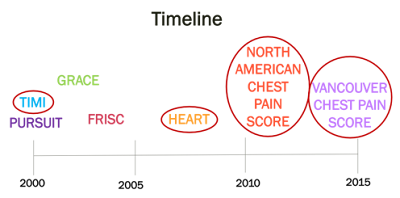

Chest pain score overview

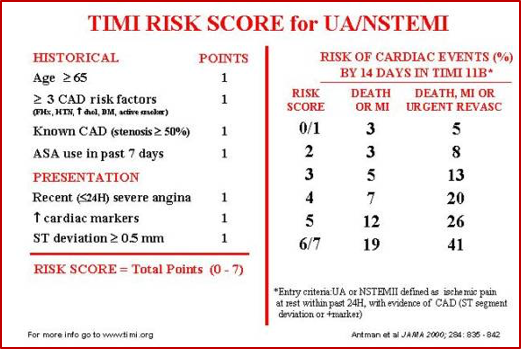

- Initially derived in ACS population.3

- Predicts the risk of death, MI, recurrent ischemia requiring revascularization at 14 days.

- Despite being initially developed for risk stratification of patients with known unstable angina or NSTEMI, this score has been broadly used and validated in several independent ED populations with chest pain.

- A meta-analysis by Hess et al. (2010) showed a strong linear relationship between TIMI score and incidence of cardiac events at 30 days.

- However, a TIMI score of 0 (i.e. a low risk TIMI score) still only had a sensitivity of 97.2% (CI:96.4%-97.8%) for predicting cardiac events at 30 days.4

Bottom Line

NORTH AMERICAN CHEST PAIN SCORE

|

| Source: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21885156 |

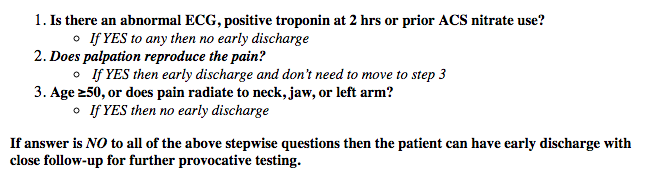

- Initially derived in a Canadian Emergency Department patient population

- The derivation and internal validation study was rigorous and had strong methodology5

- The results from the derivation study showed that 18% of people could be safely discharged using this rule with a sensitivity of 100%.5

- Although this seems pretty good, a comparison study by Mahler et al. (2012) that also showed 100% sensitivity for the rule, unfortunately only showed that only 4.4% of their sample population could be safely discharged using this score.6

Bottom Line:

Although this score was derived in a Canadian population, it unfortunately only identifies a low percentage of the population as ‘low risk’ and has not been externally validated. THIS IS NOT A SCORE THAT WE SHOULD BE USING.

VANCOUVER CHEST PAIN RULE

- Initially derived by Christenson et al. (2006) but unfortunately the rule was created using CK-MB as the primary biomarker and never really gained popularity.

- In 2014, Cullen et al. externally validated the Vancouver Chest Pain rule using TnI as the only biomarker, which is more relevant to how we assess chest pain today.

- This external validation study showed a strong sensitivity but a poor specificity for the rule using both the contemporary TnI and the high sensitivity TnI.

- C-TnI: Sensitivity 98.8% (95% CI: 97.0%-99.5%); Specificity 15.8% (95% CI:13.9%-17.9%)

- Hs-TnI: Sensitivity 99.1% (95% CI: 97.4%-99.7%); Specificity 16.1% (95% CI:14.2%-18.2%)

- Furthermore, the rule only identified 13% of patients as low risk and eligible for early discharge.

Bottom Line:

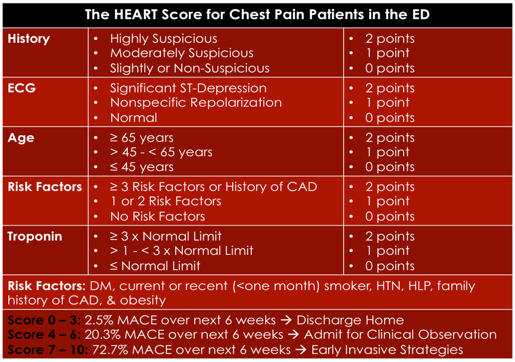

HEART SCORE

- Initially created for patients with undifferentiated chest pain in the ED from a discussion between Dr. Backus and Dr. Six.

- Goal of the score was for it to be simple and easy to use.

- First retrospective chart review done in the Netherlands.

- Findings from this study showed that the chances of reaching a combined endpoint of a MACE at 6 weeks (primary outcome), increased as the HEART score increased.

- The c-statistic for this predictive model was found to be 0.90.9

- Subsequently, a multicentre prospective external validation study was done in the Netherlands in 2013. Results showed that 36.4% of patients were able to be classified as low risk, and that those classified as low risk had a 1.7% chance of a major adverse cardiac event (MACE) at 6 weeks.

- The c-statistic from this study was found to be 0.83.10

Bottom Line:

- It was derived in the ED

- It provides a range of scores for each clinical component

- It is easy to remember

- It is the best score a differentiating low, medium and high risk patients

The disadvantages of this score are that:

- The authors did not follow standard methodology for clinical decision rule derivation

- It is possible to have a positive TnI or ECG changes and still be considered low risk (score 0-3).

Finally, a low HEART score only gives a MACE rate of 1.7% at 6 weeks, which still seems a bit high when we initially said that the acceptable miss rate for ACS by physicians is 1%. Overall, I REALLY LIKE THIS SCORE BUT WONDER IF WE CAN MAKE IT BETTER…

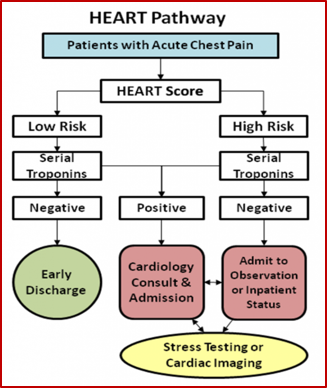

HEART PATHWAY

|

| Source: http://circoutcomes.ahajournals.org/content/8/2/195.figures-only |

- They found that when they grouped people into a ‘low risk HEART score’ they had a MACE rate of 0.6% but if a second delta TnI was added, they were able to capture all MACEs with 100% sensitivity.

- From this study the HEART Pathway was born (see above).

- Using this pathway Mahler et al thought that they could get under a 1% miss rate of ACS.11

In 2013, the same group conducted another study where they did a secondary analysis on a MIDAS cohort, which was a prospective observation cohort of ED patients enrolled from 18 US sites with symptoms suggestive of ACS who had a high event rate of ACS (22%).

Applying the HEART pathway to this cohort, the authors would have been able to discharge 20.2% as low risk with a sensitivity of 99.1% (95% CI: 96.5%-100%) and a specificity 25.7% (95% CI: 22.7%-28.9%).6

In 2015, Mahler et al. published a single centre RCT of 282 patients where they randomized patients to either the HEART Pathway or usual care pathway based on the ACC: AHA guidelines. They looked at many different measures related to efficiency and not relevant to a Canadian Emergency Department setting such as early discharge rate, median length of stay, and decreasing stress test.

-

Interestingly they found no MACE events among patients classified as low-risk by the HEART pathway. Unfortunately, this study was not powered to detect MACE rate differences.12

-

Overall, from these studies, the research group quotes that low risk HEART Pathway classification (<3 on the HEART score and a 0 and 3 hour TnI that are negative), has under 1% rate of MACE at 30 days.

-

Mahler et al. have created an app can be downloaded at the Apple App Store to help calculate HEART Pathway scores for patients in the ED.

Bottom Line:

CLINICAL GESTALT

Bottom Line:

MEDICAL-LEGAL IMPLICATIONS OF CHEST PAIN SCORES

- If you look at CMPA data in EM over the last 5 years, in cases where there is a diagnostic issue, ischemic heart disease is the number one reason for litigation.

- Consequently, although the rate of physician litigation is far less in Canada than in the United States, medical-legal implications of chest pain scores are still something that we should be aware of.

- On the CMPA website there is an article that addresses the role of clinical practice guidelines and decision tools in legal proceedings.

- This article highlights that the CMPA itself does not create nor endorse guidelines or risk scoring systems.

- However, in court physicians are judged against other physicians who are practicing the same type of medicine.

- Whether or not using a clinical score or guideline is viewed as the standard of care depends on the credibility and validity of the scoring system itself.

Ultimately, it is prudent for physicians to be aware of authoritative clinical practice guidelines and decision scores relevant to their practices.

FINAL TAKE HOME POINTS

- There are many chest pain scores with varying degrees of evidence.

- HEART Pathway is the only score with approximately a 1% MACE at 30 days.

- Clinical Gestalt performs well for patients we feel ‘definitely don’t have ACS’ and have negative TnI and ECG.

- Chest pain scores are not the standard of care but at the moment, but are an AHA/ACC class IIa recommendation.

Dr. Samantha Calder-Sprackman is a 4th year Emergency Medicine resident at the University of Ottawa and the current co-chief resident for the RCPSC program. She has a particular interest in patient safety, quality improvement and medical education.

References: