Relative to its incidence and prevalence, Lyme disease has gathered a tremendous amount of attention, particularly in the last decade or so. This can be attributed, in part, to the perceived difficulty in properly diagnosing and treating the disease. However, the bulk of its recent attention stems around controversies surrounding chronic Lyme disease. It has made its way into mainstream pop culture, celebrities are becoming increasingly vocal and activists are devout.

What is all the buzz about? As healthcare providers, we owe it to our patients to know the facts in order to provide the best care possible.

Agent / Vector

The causative agent of Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi is a tick-borne spirochetal bacteria that was discovered and named after Dr. Willy Burgdorfer. This discovery took a while… over a decade after Dr. Allen Steere began his investigation into an unusual cluster of suspected juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in Lyme, Connecticut1. There are other species of Borrelia (B. garinii and B. afzelii in Europe & Asia that cause a different spectrum of Lyme disease than in North America, not discussed here).

Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus are the ticks in North America that carry Lyme disease2. Important reservoirs include field mice (amplifying host), birds and white-tailed deer. The other common tick-borne illnesses are transmitted through the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) and the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis) that transmit ehrlichiosis and Rocky Mounted spotted fever, respectively3.

Endemicity

Lyme disease is endemic in the Northeastern and North Central United states and incidence is rising. In Canada, Lyme disease is found virtually everywhere, except in Alberta and in the far North. Ontario’s high risk zones are mostly localized to the St. Lawrence river valley. For more information, visit the Health Canada’s Lyme Disease website.

Identification and Risk of Transmission

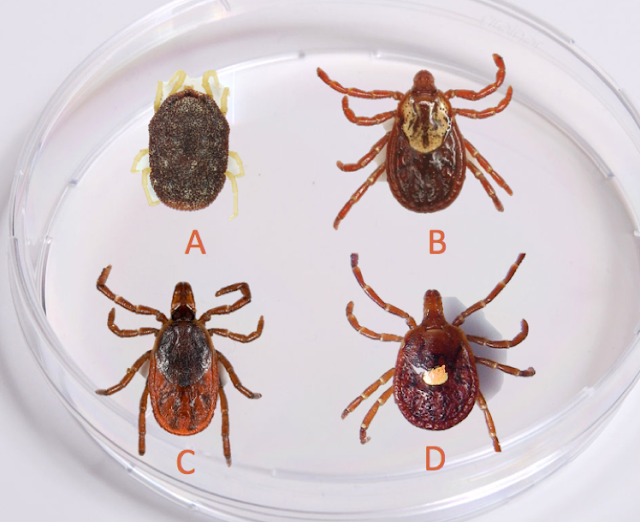

Since Ixodes scapularis is the tick responsible for Lyme disease, part of our risk assessment for transmission of Lyme disease can include identification of the tick (if the patient brought the tick in). Ixodes scapularis are hard ticks, and therefore have a scutum (shield). Their bodies are long and they have long mouth parts. See if you can identify which one of the following is Ixodes scapularis – see below for answers, try not to cheat!

So, which one was Ixodes scapularis?

A) is an Argasid (soft tick, Ornithodoros turicata)

B) has a scutum, long body but short mouth parts (dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis)

C) is Ixodes scapularis (!)

D) has a scutum, but has a short and stout body – it also has a “lone star” on its body (lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum)

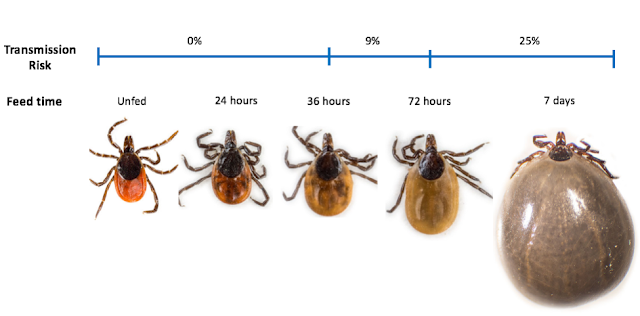

The risk of transmission is highly unlikely if the tick has been attached for less than 36 hours, which directly correlates with the tick’s level of engorgement4.

A 2001 study by Nadel et al. demonstrated the risk of developing Lyme disease (in a Lyme hyper-endemic area) according to tick engorgement as follows:

· No engorgement: 0%

· Some engorgement: 9%

· High engorgement: 25%

· All tick bites: 3%

For those who are more visual:

Clinical Manifestations

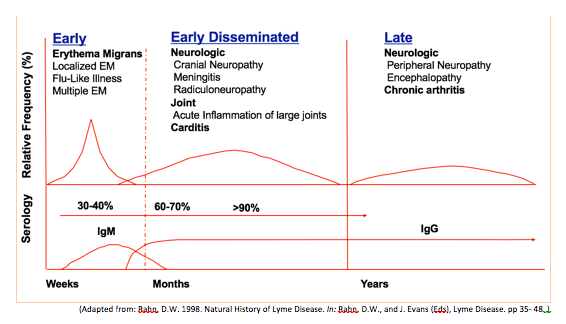

The clinical manifestations can be divided into three stages: early, early disseminated and late disease. These are summarized graphically below.

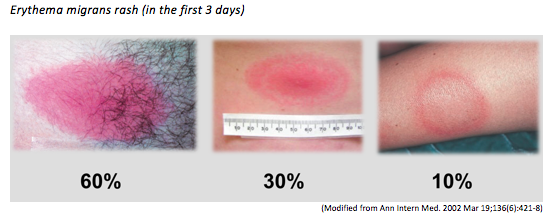

The hallmark of early Lyme disease is the early localized manifestation of an erythema migrans rash, which is found or noticed in around 80% of patients (see below). The rash is typically a round/oval expanding erythematous macule that presents within 3-30 days at the site of the tick bite that may or may not have central clearing. It is usually >= 5 cm in diameter and there can be multiple lesions, indicating a locally disseminated disease. It is not typically itchy or scaly. A viral syndrome is variably associated with the rash2.

Early disseminated and late Lyme disease are characterized by cardiac, neurologic and joint manifestations. An important point of consideration is that some patients may have symptoms from one stage of the disease without having symptoms of an earlier stage.

Key points on clinical manifestations2

Early Disease

- Erythema migrans is pathognomonic for diagnosis

- May have multiple lesions — Serologic testing likely negative at this point (no role for testing)

- A rash that appears within 2 days of tick removal is very likely a local allergic to the antigens in the tick saliva

- Often does not have central clearing or “bullseye” appearance

Early Disseminated

- Neurologic Disease

- CN VII palsy is most common (Bilateral CN VII palsies essentially confirms Lyme disease)

- Meningitis is a lymphocytic meningitis similar to viral meningitis, but the presentation is subacute (usually presents at ~ 1 week)

- Late neurologic manifestations can include a subtle encephalopathy and peripheral neuropathy

- Cardiac Disease

- Mild pericarditis and sometimes high grade AV block

- Joint Disease

- Inflammatory monoarthritis with large joint effusions (knees, shoulder, elbow, TMJ, wrist)

- May be asymmetric oligoarthritis or arthralgias alone

- Late disease can include chronic arthritis

Serologic testing is almost universally positive at this point

Think about Lyme disease and ask about tick exposure in patients with CN VII palsy, subacute meningitis, AV block or large joint effusions in the warmer months!

How do we test for it?

In Canada, the only accepted test method for Lyme disease is a two-tiered serology.

Step 1: Sensitive ELISA IgM/IgG

· Has poor specificity due to cross-reactions (SLE, RA, viral illnesses)

· If negative, patient is considered to have negative test

· If positive, move on to Step 2

Step 2: Specific Western blot

· Specific interpretative criteria described by CDC

· Not applicable for European Lyme disease

· Positive test = evidence of encounter with Borrelia burgdorferi

Special considerations6:

· If > 4 weeks since infection and IgM positive and IgG negative, very likely false positive

· Seropositivity can persist for years after Lyme disease treated and cured

· Must take seropositivity into clinical context

· Must specify if patient may have been infected outside of North America – lab will use different diagnostic criteria for different strains

Tests that are considered unreliable7,8:

· PCR

· Urine antigen test

· Blood smears

· T-cell proliferation assays

· Immune complex assays

· Serology that deviate from accepted methods

o High false positive rates

o Inter-laboratory variability

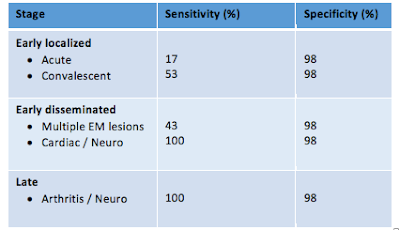

How does the two-tier serologic test perform?

Much of the controversy of Lyme disease testing stems from understanding of the test characteristics. In short, the test isn’t very sensitive early on, while the test has a very high specificity in disseminated and late disease6. This is true for virtually all antibody-dependent testing.

Who should we test?

Although the test has high specificity in late disease, clinicians should be judicious about testing patients for Lyme disease since false positive rates are increasingly probable when the pre-test probability for Lyme disease is very low9.

The CDC recommends testing patients if ALL of the following are satisfied:

1. Residence or travel to a Lyme endemic area

2. Risk factor for exposure to ticks

3. Symptoms consistent with early disseminated disease or late disease (neurologic disease, carditis, arthritis)

Erythema migrans in a patient with possible tick exposure in a Lyme endemic

area confirms the diagnosis of Lyme disease.

Do NOT test patients with erythema migrans as the test will very likely be negative.

Acute and convalescent titres may be considered only when there is clinical uncertainty.

What is considered a confirmed case? (CDC definition)

1. Erythema migrans plus known exposure

2. Erythema migrans (without clear exposure) plus positive serology

3. Neuro, cardiac, joint disease consistent with Lyme disease plus positive serology

Prophylaxis

Concerns around tick bites and prophylaxis are the most common Lyme-related ED

presentation. As mentioned above, the risk of transmission is exceedingly low if the tick

has been attached less than 36 hours (by time or degree of engorgement). Furthermore,

the tick must have been Ixodes scapularis.

That said, here are the IDSA recommendations for prophylaxis:3

Doxycycline 200 mg PO x 1 (same dose for children > 8 years) when ALL of the

following:

-

- Ixodes scapularis tick

- Tick attached >= 36 hours (by time or engorgement)

- Prophylaxis w/in 72 hours of tick removal

- Local tick infection rate with B. burgdorferi >= 20%

- Doxycycline not contraindicated

If there is a contraindication to doxycycline, the IDSA recommends a watch and wait approach since:

1. There is no data support efficacy of a short course of another antibiotic

2. Longer courses of antibiotics = more side effects

3. If Lyme disease does develop, treatment outcomes are excellent

4. Extremely low risk that a person with recognized bite will develop a serious complication of Lyme disease

Chronic Lyme Disease

Chronic Lyme disease is… complicated. In some cases, Lyme disease does not cause objective symptoms, such as Lyme arthralgia without arthritis and subtle Lyme encephalopathy10.

Furthermore, up to 10% of patients with proven Lyme infection go on to have persistent subject symptoms (fatigue, arthralgias, cognitive slowing, paresthesias) months to years later11,12. It’s not clear what causes these symptoms, but the best explanations relate to autoimmune dysfunction following Lyme disease.

Then, the serologic testing (as mentioned previously) is insensitive in early stages of the disease, and although very specific in late disease, may produce high false positive rates when the test is performed in low pre-test probability scenarios.

When you factor in the fact that 2% of the general population suffers from chronic fatigue symptoms, the result is a lot of people who believe they have chronic Lyme disease and that conventional medicine has failed them13. The following have spawned as a result:14,15

· “Lyme literate MDs”

· Private labs with alternate diagnostic criteria

· Pseudoscience and alternative treatments

· Protracted antibiotics

· Political and medical activism

Political and medical activism has essentially shaped up into a battle dubbed as the “Lyme Wars”, which pits the IDSA stance against the Lyme activist group ILADS (International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society)16.

The IDSA stance:

· Lyme disease is rare and geographically localized

· Difficult to catch

· Co-infections uncommon

· Easily diagnosed by clinical features and accurate standardized lab testing

· Easy to treat and cure

· Chronic infection is rare or non-existent

The ILADS stance:

· Lyme disease is not rare

· Can be found anywhere

· Co-infections common

· Tick bites/EM often go unnoticed

· Commercial lab testing rife with false negatives

· Chronic infection does exist

· Disease either unrecognized or persists in large number of patients and requires prolonged antibiotic therapy to eradicate persistent infection

Without going into too much detail here, the “war” continues today. Research continues to answer important questions about cause, diagnosis and treatment. While the evidence is heavily set against chronic infection with Borrelia burgdorferi as a cause for chronic subjective symptoms after Lyme infection, it’s not a slam dunk.

Summary: What we know about chronic Lyme disease

1. Some patients (10-15%) develop persistent subjective symptoms after confirmed Lyme.17,18… and the cause remains an area of uncertainty

2. 2% of non-Lyme affected patients in the general population have the same symptoms.3,19–21

3. Most patients claiming they have chronic Lyme disease have never had objective serologic or clinical diagnosis.14,22,23

4. The false positive rate for private labs (such as IGeneX) are very high; the serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease should use the CDC criteria for Western blots.8

5. There is some evidence to suggest B. burfdorferi may persist in infected hosts, but its role in chronic disease is not clear.24–27

6. Seronegative Lyme disease is extremely rare in late disease.28

7. Co-infection with babesiosis or anaplasmosis do not play a role in the vast majority of cases.29

8. Protracted antibiotics have not been shown to help in multiple RCTs and shouldn’t be part of the solution.23,30–33

9. Pseudoscience and alternative treatments have not been shown to help, and in some cases have caused serious to harm to patients, including death.15

My synthesis:

· Available evidence does not support persistent infection as the cause of post-Lyme syndrome, but it’s not impossible.

· Protracted antibiotics are not the answer.

· If your patient hands you a report from a private lab like IGeneX, look at the CDC result interpretation, and nothing else.

· Our job in the ED

o Recognize objective Lyme

o Avoid/suppress preconceptions

o Treat new problems like any other

o Refer patients who believe they have chronic Lyme disease to a provider capable of spending an appropriate amount of time to discuss symptoms, diagnosis and treatment. This could be their GP or a consultant in infectious diseases.

Take home points

1. Remember the indications and rationale for Lyme disease prophylaxis

2. Erythema migrans is often appears as a red macule and not a bullseye rash in the first few days.

3. If you see a patient with a viral syndrome, carditis, neuritis (facial nerve palsy, subacute meningitis) or arthritis in the warm months, stop and ask yourself if this could be Lyme disease.

4. There exists some uncertainty with chronic Lyme disease, and controversies surrounding chronic Lyme disease are far from over.

Dr. Michael Ho is a 5th year Emergency Medicine resident with the University of Ottawa. He has a particular interest in education, critical care and ultrasound.

Edited by Dr. Robert Suttie, PGY-2 Emergency Medicine Resident at the University of Ottawa

References

1. Steere AC, Grodzicki RL, Kornblatt AN, et al. The spirochetal etiology of Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1983;308(13):733-740. doi:10.1056/NEJM198303313081301.

2. Shapiro ED. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(18):1724-1731. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1314325.

3. Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(9):1089-1134. doi:10.1086/508667.

4. Spielman A, Ribeiro JMC, Mather TNN, Piesman J. Dissemination and salivary delivery of lyme disease Spirochetes in vector ticks (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 1987;24(2):201-205. doi:10.1093/jmedent/24.2.201.

5. Smith RP, Schoen RT, Rahn DW, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcome of early Lyme disease in patients with microbiologically confirmed erythema migrans. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(6):421-428. doi:200203190-00005 [pii].

6. Branda J a, Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Ferraro MJ, Johnson BJB, Wormser GP, Steere AC. 2-tiered antibody testing for early and late Lyme disease using only an immunoglobulin G blot with the addition of a VlsE band as the second-tier test. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:20-26. doi:10.1086/648674.

7. Klempner MS, Schmid CH, Hu L, et al. Intralaboratory reliability of serologic and urine testing for Lyme disease. Am J Med. 2001;110(3):217-219. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00701-4.

8. Dattwyler RJ, Arnaboldi PM. Editorial commentary: Comparison of lyme disease serologic assays and lyme specialty laboratories. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(12):1711-1713. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu705.

9. Lantos PM, Branda JA, Boggan JC, et al. Poor positive predictive value of lyme disease serologic testing in an area of low disease incidence. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(9):1374-1380. doi:10.1093/cid/civ584.

10. Steere AC, Schoen RT, Taylor E. The clinical evolution of lyme arthritis. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107(5):725-731. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-107-5-725.

11. Luger SW, Paparone P, Wormser GP, et al. Comparison of cefuroxime axetil and doxycycline in treatment of patients with early Lyme disease associated with erythema migrans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39(3):661-667. doi:10.1128/AAC.39.3.661.

12. Shapiro ED. Clinical practice. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(18):1724-1731. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1314325.

13. Luo N, Johnson J a, Shaw JW, Feeny D, Coons SJ. Self-reported health status of the general adult U.S. population as assessed by the EQ-5D and Health Utilities Index. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1078-1086. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000182493.57090.c1.

14. Lantos PM. Chronic Lyme disease: the controversies and the science. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2011;9(7):787-797. doi:10.1586/eri.11.63.

15. Auwaerter PG, Bakken JS, Dattwyler RJ, et al. Antiscience and ethical concerns associated with advocacy of Lyme disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(9):713-719. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70034-2.

16. Stricker RB, Johnson L. Chronic Lyme disease and the “Axis of Evil”. Future Microbiol. 2008;3:621-624. doi:10.2217/17460913.3.6.621.

17. Feder H, Johnson B. A critical appraisal of “chronic Lyme disease.” N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1422-1430. doi:10.1056/NEJMra072023.

18. Wormser GP, Weitzner E, McKenna D, et al. Long-term Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Culture-Confirmed Early Lyme Disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(2):244-247. doi:10.1093/cid/civ277.

19. Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, Russell IJ, Hebert L. The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(1):19-28. doi:10.1002/art.1780380104.

20. Nadelman RB, Nowakowski J, Fish D, et al. Prophylaxis with Single-Dose Doxycycline for the Prevention of Lyme Disease after an Ixodes scapularis Tick Bite. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(2):79-84. doi:10.1056/NEJM200107123450201.

21. Seltzer EG, Gerber MA, Cartter ML, Freudigman K, Shapiro ED. Long-term outcomes of persons with Lyme disease. JAMA. 2000;283(5):609-616. doi:10.1089/153036602321653879.

22. Steere a C, Taylor E, McHugh GL, Logigian EL. The overdiagnosis of Lyme disease. JAMA. 1993;269(14):1812-1816. doi:10.1001/jama.1993.03500140064037.

23. Klempner MS, Baker PJ, Shapiro ED, et al. Treatment trials for post-lyme disease symptoms revisited. Am J Med. 2013;126(8):665-669. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.02.014.

24. Embers ME, Barthold SW, Borda JT, et al. Persistence of borrelia burgdorferi in rhesus macaques following antibiotic treatment of disseminated infection. PLoS One. 2012;7(1). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029914.

25. Livengood JA, Gilmore RD. Invasion of human neuronal and glial cells by an infectious strain of Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbes Infect. 2006;8(14-15):2832-2840. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2006.08.014.

26. Kersten A, Poitschek C, Rauch S, Aberer E. Effects of penicillin, ceftriaxone, and doxycycline on morphology of Borrelia burgdorferi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39(5):1127-1133. doi:10.1128/AAC.39.5.1127.

27. Preac-Mursic V, Wilske B, Gross B, et al. Survival of Borrelia burgdorferi in antibiotically treated patients with lyme borreliosis. Infection. 1989;17(6):355-359. doi:10.1007/BF01645543.

28. Steere AC, McHugh G, Damle N, Sikand VK. Prospective study of serologic tests for lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(2):188-195. doi:10.1086/589242.

29. Lantos PM, Wormser GP. Chronic coinfections in patients diagnosed with chronic lyme disease: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2014;127(11):1105-1110. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.05.036.

30. Klempner MS, Hu LT, Evans J, et al. Two controlled trials of antibiotic treatment in patients with persistent symptoms and a history of Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(2):85-92. doi:10.1056/NEJM200107123450202.

31. Krupp LB, Hyman LG, Grimson R, et al. Study and treatment of post Lyme disease (STOP-LD): a randomized double masked clinical trial. Neurology. 2003;60(12):1923-1930. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000071227.23769.9E.

32. Fallon BA, Keilp JG, Corbera KM, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of repeated IV antibiotic therapy for Lyme encephalopathy. Neurology. 2008;70(13 PART 1):992-1003. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000284604.61160.2d.

33. Berende A, ter Hofstede HJM, Vos FJ, et al. Randomized Trial of Longer-Term Therapy for Symptoms Attributed to Lyme Disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1209-1220. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1505425.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks