Traumatic Cardiac Arrest

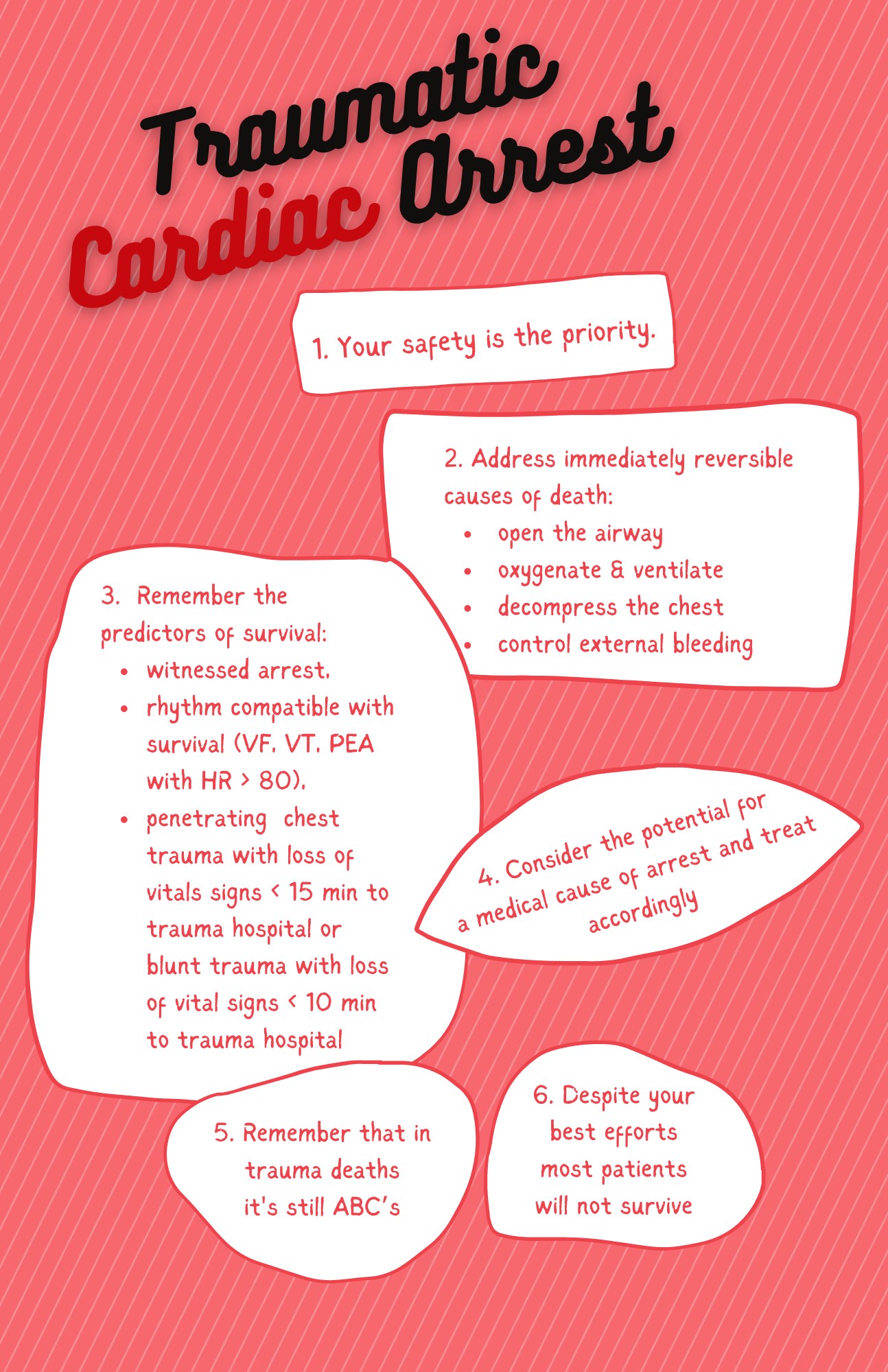

Paramedics often respond to patients who have no vital signs after being involved in a traumatic event. These cases are especially notable for the tragic and violent means by which persons suddenly meet their end. Most patients who do not have vital signs after trauma will not survive. The role of the paramedic is to rapidly determine if there are any immediately reversible causes of death that can be safely addressed in the field or a trauma hospital. Unfortunately, we do not have the same evidence to guide our decision-making for traumatic cardiac arrest that we do for medical cardiac arrests. Nevertheless, we do know why patients who experience trauma die, and as such we know the common preventable causes of death. It is this latter pathology that prehospital providers must be experts at identifying and treating.

“We know why patients who experience trauma die and the common preventable causes of death”

What are the immediate causes of death after trauma?

When you arrive at the scene of an acute trauma and a patient is dead or taking their last breaths, the cause of death is usually one of three pathologies: catastrophic brain injury, high cervical spine injury (both of which cause apnea), and trauma aortic injury (causing rapid exsanguination). (1)

These injuries along with the associated pathology are typically not survivable. Often patients are pronounced dead at the scene and the cause of death is determined at autopsy.

Another important cause of immediate death that we have learned about through motorsports racing medicine is a condition called concussive apnea, in which somebody sustains a head injury significant enough to cause loss of consciousness and apnea, followed by hypoxia and a resulting cardiac arrest if they do not recover their breathe. (2) The etiology of the apnea can be from loss of airway patency from being obtunded, to respiratory depression from the concussion, or a combination of the two. The effects of this condition seem to be compounded by acute alcohol intoxication (think about the trend of “one-punch” deaths in front of the bar at 2 am). (3)

When the airway is opened and breathing is provided in a timely way, many of the victims of this condition go on to resume spontaneous breathing, regain consciousness and have no permanent brain injury.

The importance of recognizing and treating this syndrome should be self-evident to any first responder, and it is one of the reasons we recommend most patients without vital signs after a head injury undergo a trial of resuscitation that includes opening the airway and providing ventilatory assistance.

What are the preventable causes of death after trauma?

A search for rapidly reversible causes of death is important before considering terminating the resuscitation. Much of what we know about treatable causes of preventable death from trauma in the field comes from military literature (4), but there is some civilian literature to draw from as well (5).

The most common preventable causes of death are uncleared airway obstruction, tension pneumothorax, and hemorrhage. To the best of your ability, ensure a patent airway, provide ventilation with oxygen, decompress the chest if you have a clinical concern for tension pneumothorax, and control external bleeding with pressure and tourniquets. Note that this approach is very different than the one recommended for sudden cardiac death, accounting for the different etiology of cardiac arrest in trauma patients (airway, breathing, bleeding) vs medical patients (sudden cardiac arrhythmias treated with chest compression and defibrillation).

There is no one-size-fits-all strategy for cardiac arrest and your expert clinical judgement is required.

If spontaneous circulation cannot be established after these interventions, it’s unlikely the patient will survive. How long should the resuscitation continue before determining futility? That’s a matter of controversy. The National Association of EMS Physicians issued a statement in 2012 indicating that up to 15 minutes of CPR should be provided before determining futility (6).

Often, Advanced Life Support (ALS) Patient Care Standards (PCS) don’t provide this in many trauma cases. This highlights the controversy of CPR in a traumatic arrest and the need for further study on the issue. Being aware of this uncertainty, provides rationale as to why the Base Hospital Physician (BHP) might suggest further resuscitation even though the ALS PCS recommended calling to consider termination of resuscitation (TOR). As in cases of medical cardiac arrest, there may be cases where the BHP agrees that transportation with CPR is not going to be helpful, but a trial of further resuscitation at the scene is warranted before terminating resuscitation.

What are the predictors of survival after trauma?

While the vast majority of patients who suffer cardiac arrest from trauma will not survive despite resuscitation, there are some studies that provide insight into the predictors of survival.

When patients have a cardiac arrest witnessed by paramedics, that is, vital signs are documented at the scene, the survival rate is 2-4% with resuscitation and transport. (7) Survival rates have also been documented for patients who have cardiac rhythms that are compatible with survival (VF, VT, PEA with a rate >80 bpm). In the case of ventricular arrhythmias, the paramedic must ask themselves, could a medical event have precipitated the “trauma”?

Think of the scene in which a car is witnessed to slowly drift off the road. There is a collision, but forces and injuries are not consistent with the patient’s presentation, and they are in VF – could this be a medical arrest? The prognosis for a patient with a witnessed VF arrest is certainly very different than the one for a patient who is VSA from blunt force trauma. Your judgement is required here, and if in doubt please err on the side of resuscitating.

The trauma patient with PEA with a normal or fast and narrow electrical rate could simply be so hypotensive that a pulse cannot be appreciated. In the prehospital world, this type of patient warrants an aggressive search for immediately reversible causes. Patients presenting with asystole have a <1% chance of survival, and it is often reasonable to terminate resuscitation early if you are confident there is nothing immediately reversible like airway obstruction, concussive apnea or tension pneumothorax. Patients with slow PEA also have a low probability of survival but warrant a resuscitation attempt if feasible to treat any reversible causes and attempt to establish ROSC.

Patients with penetrating trauma to the chest and loss of vital signs within 15 minutes of the trauma hospital are also a group with a greater chance of survival than other trauma arrests. In addition to airway management and chest decompression, these patients may benefit from an Emergency Department thoracotomy where the pericardial sac is drained to relieve tamponade, holes in the heart are plugged, and the descending aorta is cross clamped to help get control of bleeding. A similar approach may be considered for blunt trauma patients with loss of vital signs within 10 minutes of the trauma hospital. This will depend on a number of factors, not least of which is the capabilities of the receiving hospital. The trauma team at The Ottawa Hospital (and other trauma hospitals) uses the time-based cutoffs outlined in the Western Trauma Association guidelines to determine eligibility for ED thoracotomy (8). Be prepared to rapidly transport patients in these circumstances, especially if you are close to a trauma hospital.

“Patient with penetrating trauma to the chest and loss of vital signs who are within 15 minutes of a trauma hospital have a greater chance of survival than others with trauma arrests.”

When is withholding resuscitation of a potentially salvageable patient appropriate?

It’s important to remember personal safety of all prehospital providers at the scene of a trauma. If it is not safe to resuscitate a patient with no vital signs, termination of resuscitation should be entertained.

Another circumstance to consider is the scene of a mass casualty incident (MCI), where there are not enough resources to look after the patients present. In these circumstances prehospital providers implement an MCI triage. If a patient with no vital signs does not start breathing with a basic maneuver to open the airway, you tag them “black” and move on to the next casualty. All “black” tagged individuals can be reassessed if and when resources become adequate. The exception to this would be an MCI with electrocution and VSA patients, where attempts should be made to restore circulation with ACLS, as patients who are alive after electrocution are likely to remain alive, and patients who suddenly die from electrocution can be amenable to quick treatments like defibrillation.

What are some other considerations?

Patients who are trapped after blunt trauma and believe to be VSA, but who are difficult to access, pose a particular challenge. On one hand paramedics may be reticent to ask fire departments to undertake rapid attempts to access a patient when the scene is not safe, and extrication is going to be prolonged or seemingly impossible. On the other hand, there is an imperative for a trained professional to access the patient to determine that there are no vital signs (after clearing and opening the airway if possible), and ideally obtaining a cardiac rhythm, prior to determining that irreversible death has occurred. In these cases, BHPs are likely to ask that a first responder access the patient and confirm no vital signs prior to giving a withhold resuscitation order.

In all cases the safety of first responders is paramount.

Another challenge is the unwitnessed trauma patient who is found to be VSA and cold. Did the patient die and then cool because they are dead? Or, did they die due to exposure and are hypothermic? The first category is clearly deceased, whereas the second may benefit from resuscitation and rewarming.

Some clues at the scene that may assist in this determination are a mechanism and physical exam findings consistent with lethal trauma. A history of incapacitation (alcoholism, dementia, developmentally delayed/pediatric) or a survivable injury that limits mobility could all raise the possibility of a primary hypothermic event. It may not be possible in the field to sort this out. If in doubt, transfer to hospital with ongoing CPR is appropriate.

And finally a quick word about patients who die from asphyxiation. These patients can be seen after hangings, drownings, carbon monoxide poisonings, physical restraint during violent confrontations, and airway obstruction and apnea from head and face injuries (see concussive apnea above). It cannot be emphasized enough that these arrests are different than a sudden cardiac death where the etiology is often a fatal cardiac arrhythmia and the treatment focuses on chest compressions and defibrillation, with airway management deemed less important for outcome. In deaths from asphyxiation careful attention must be paid to early and effective airway management to oxygenate the blood. Without this effort the patient will not be resuscitated.

“In deaths from asphyxiation, careful attention must be paid to early and effective airway management to oxygenate the blood.”

Final Thoughts

Traumatic cardiac arrest calls are some of the most difficult events prehospital providers and paramedics respond to. Patients who were alive and well one moment meet an untimely end, often in tragic and violent circumstances, and it is emergency responders who bear witness. While most of these patients will not survive, there is a measurable survival rate. Remembering the predictors of survival is essential to make a good initial attempt at resuscitation.

Sometimes it will bear fruit.

“Please feel free to patch early to consult on decisions around withholding or terminating resuscitation”

References

1 Hoyt D, Rotondo M: Advanced Trauma Life Support Student Course Manual. Chicago, IL, American College of Surgeons, 2012.

2 Wilson M, Hinds J, Grier G, et al.: Impact brain apnoea – A forgotten cause of cardiovascular collapse in trauma. Resuscitation. 2016;105;52-48.

3 Ramsay D: Ethanol, Trauma, and the Brain. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2014;4(2):188-197.

4 Kotwal R, Montgomery H, Kotwal B, et al.: Eliminating Preventable Death on the Battlefield. Arch Surg. 2011;146(12):1350-1358.

5 Beck B, Smith K, Mercier E, et al.: Potentially preventable trauma deaths: A retrospective review. Injury. 2019;50:1009-1016.

6 The National Association of EMS Physicians and American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma: Termination of Resuscitation for Adult Traumatic Cardiopulmonary Arrest. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2012;16(4):571.

7 Millin M, Galvagno S, Khandker S, et al.: Withholding and termination of resuscitation of adult cardiopulmonary arrest secondary to trauma. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2013;75(3):459-467.

8 Burlew C: Western Trauma Association Resuscitative Thoracotomy Algorithm. Available at https://www.westerntrauma.org/wp-content/ uploads/2020/08/Resuscitative-Thoracotomy_FINAL.svg . Accessed January 2nd, 2022.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks