For many of us in Emergency Medicine, PTSD is something we don’t really think about. We might pause before using ketamine for sedation in a war veteran, or seek psychological support for victims of sexual assault, but it is not a topic that we usually discuss or associate with. It certainly isn’t something that we feel threatens us and our careers.

However studies using standardized and validated tools have shown a point prevalence of PTSD in German [1] and Belgian [2] emergency physicians, Dutch hospital physicians [3] and Vancouver ED staff [4] to be approximately 15%. By comparison, the lifetime prevalence of PTSD in the Canadian population is approximately 2.4% [5] so a point prevalence of 15% is extremely high.

Though initially surprising, these numbers start to make sense when we think about the types of cases that emergency physicians handle regularly: pediatric injuries and arrests, sexual assaults, graphic traumas, failed resuscitations. We are exposed daily to things that would scar most people.

And yet we do not talk about occupational stress injuries, do not train for resiliency, and often fail to recognize distress in a colleague and even in ourselves. After all, we are physicians, we should be better and stronger than this right?

So we push on, maybe drink more than we should when we come home, start having disruptive interactions with colleagues, the quality of our work diminishes, we may get complaints or litigation, we bring our stress home and our personal relationships suffer. All along often without seeking help, and often without fully realizing what is occurring.

These occupational injuries can be the result of a multitude of cumulative difficult cases combined with personal challenges and shift work, or they can occur as a result of a particularly marking case. We have all had cases that profoundly impacted us in some way. What made these cases particularly scarring? Though some are more obvious, like pediatric deaths and severe traumatic injuries, there are a number of more subtle reasons for us to get injured by a case that may seem relatively innocuous to another person. Pre-existing stress, ongoing work stressors, recent cumulative difficult cases, poor coping habits and substance use, limited social support all affect how we process the emotional impact of emergency cases [6,7,8]

Another factor that is often overlooked is relatability of the patient – if they look like a loved one, are the same age as our child, etc, the case can cause the provider distress that may appear disproportionate to the pathology.

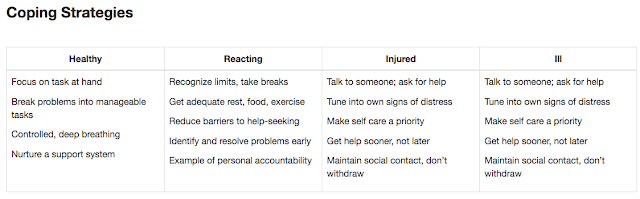

This is not to say that occupational injury is inevitable in our profession or that we are all bound to become scarred by our practice. The most common pattern of adjustment after potentially traumatic events is resilience or recovery [9]. Resilience building, self-care and early interventions after critical incidents may play a role in primary prevention of PTSD and occupational stress injuries [10, 11, 12] but first and foremost we have to acknowledge that any of us could be impacted and learn to recognize early symptoms of distress in ourselves and in our colleagues.

Strategies to mitigate the impact of critical incidents exist but they have been largely implemented and studied in military and first line providers. Critical Incident Stress Management and Debriefing was developed in 1983 by Mitchell [13]. Variants of this model were later implemented across a large number of EMS services but often with modifications. Debriefing sessions were usually considered mandatory and the program was usually only partially implemented, with all the emphasis placed on post-incident debriefing and loss of the preparation, spiritual and family supports among others.

This version of the model did not show any evidence of decreasing the rate of PTSD after critical incidents and may have caused injury in some workers. It has now fallen out of favour but I think there are some lessons to learn from it:

- First, support and care for the provider as a whole, including family support and prevention strategies should play an important part of any critical incident management program.

- Secondly, it is important to respect each provider’s own coping methods and not force anyone to participate in any debriefing or conversation about the incident if they are not inclined to do so.

A Canadian survey of EMS providers was done by Halpern in 2006 that for the first time asked first line providers what they found most helpful after a critical incident [14]. They found that a brief time-out period after an incident, support from management and being given the opportunity to discuss with people of their choosing if and when they feel comfortable were the most beneficial interventions.

Emerging critical incident management strategies seem to follow that approach of providing support and letting providers use their established coping mechanisms rather than being intrusive and forcing unwelcome discussions. Psychological First Aid [15] is based on this principle and is becoming the most commonly used program by international organizations however it is designed for and best suited to disaster relief and is not entirely suitable for health care providers.

The British marines have developed the Trauma Risk Management (TRiM) [16] program which incorporated peer support groups within platoons who check in on their peers 3 days and 1 month after a critical incident and are trained to recognize early signs of psychological injury. While this program is not entirely applicable to our environment, the idea of having a formal peer-support group that is expected to check in with their co-workers if they hear there has been a difficult case is very interesting.

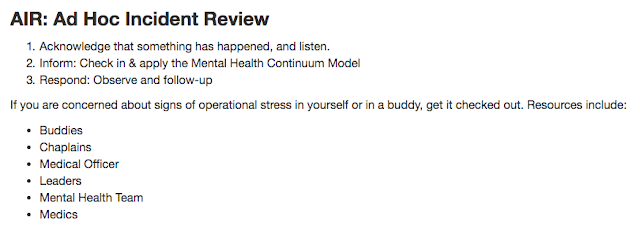

Perhaps the most compelling program at this time however is the Canadian DND “Road to Mental Readiness” (R2MR) which has also been adapted for civilian police and EMS and is quickly gaining popularity. It focuses largely on resilience building and strengthening support systems as well as destigmatization. Post incident ad-hoc reviews acknowledging that a critical incident has occurred and encouraging (but not mandating) discussion, as well as post-incident down time are emphasized.

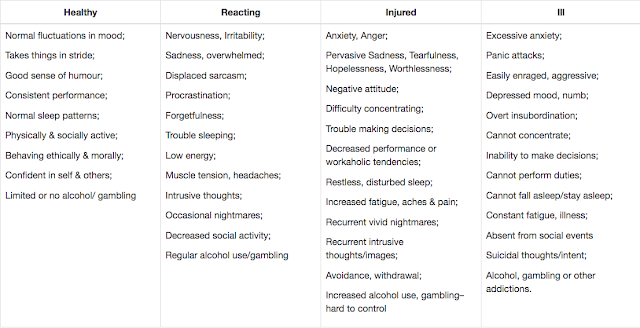

Perhaps most importantly, each member is trained to apply the “mental health continuum” to recognize signs of distress in themselves, their peers, and their subordinates. This program is quite promising for health care providers and could very well be adapted and incorporated in medical education.

I happened upon this post after waking up at 1:30 AM after a troubling dream that seemed to be a mix of several cases from my past. I am a just retired emergency physician who well remembers walking out of the Ottawa Civic 38 years ago on the last day of my emergency medicine residency. There were no support groups then, or even a well structured program and my instructors were only a couple of years older than I was. No one felt the need to debrief, or inquire into the well-being of a colleague. The “lone ranger” mentality that keeps us going was strong and the only advice given was to just “suck it up”. That worked for most of us, for most of our careers. Emegency medicine has a hidden secret, however, and that is what happens to us as we age and the shifts are just as long; the shock, sadness and horror just as real; the world outside of the ED just as oblivious. My request to our academics, is to look beyond the recent trauma; look beyond the obvious signs of a stressed out colleague; start looking at what happens after 20, 30 or more years of life in the “pit”. I have known many emergency physicians in my career and truly believe a number of them carry some serious scars based on their career choice. They deny it and laugh, but there seems to be a melancholy about them that may be more than just my imagination. Our specialty is so young that we have limited experience with the generation that went before. I would propose that your research expand into the older members of our specialty and perhaps learn lessions that may help our young residents when they wake at 1:30 AM 38 years from now, reliving events of the distant past.