Opioid and narcotic abuse has been a problem in Canada for some time, but nothing compares to the rapid sweep of opioid-related deaths and hospitalizations that have occurred over the past 2-3 years.

While at one time, this problem was limited to a few pockets on the west coast, we now face an undeniable crisis of opioid abuse across the entire nation.

As ED physicians, we find ourselves fighting on the front-lines of a rapidly evolving battle, treating a once-straightforward toxidrome that is now barely recognizable, and increasingly impenetrable to our usual therapies. The demands on our departments and our clinical abilities are higher than ever, and continuing to increase- so how can we prepare for what is to come?

The goal of this post is to give you some essential information about the opioid crisis, understand the weight of the problem at hand, and give you some new clinical pearls to help aid your management of challenging opioid-related ED visits.

The Scale of the Problem

The rapidity with which this problem has grown and spread across the country is shocking. In Vancouver’s St. Paul’s ED, arguably the epicenter of the crisis in Canada, hospitals are routinely seeing 20-30 opioid overdoses per day. National data suggests that the rest of the country is not far behind.

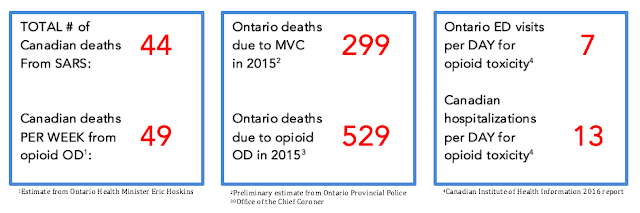

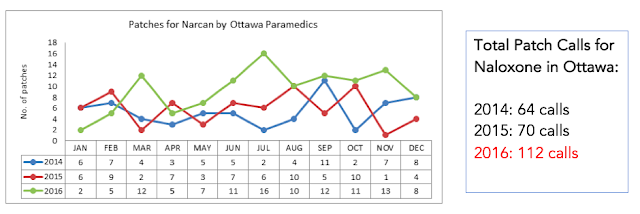

Here are a few staggering facts to help put the scale of this crisis into perspective:

From our pre-hospital data, we are seeing a massive trend towards increasing calls for overdose, and increasing demand for naloxone:

All that to say that this problem is real, and this problem is big. Convinced?

Managing an Opioid overdose

Most of us are familiar with the basic principles of managing an opioid OD, but in the context of new, high potency opioid formulations, there are a few pearls and nuances worth integrating into your practice. Here are a few key points:

ABCs: Same as always, no major surprises here.

- Remember that BVM with a good seal will save your apneic or bradypneic patient until you can get an antidote on board. It keeps them ventilating, prevents CO2 narcosis, and can help you avoid an intubation.

- Also don’t forget COMPLETE exposure – nobody wants to be the doc who intubates a refractory opioid-toxic patient without noticing the fentanyl patch on their back!!

Urine toxicology screens: Don’t send these! They’re clinically unhelpful, difficult to interpret, and should never change your management in the ED. Having said that, remember that many high potency narcotics, including fentanyl and methadone, will NOT show up on a standard urine opioid screen. If the patient looks like a clinical opioid OD, don’t let a negative urine screen steer you off course!

Naloxone

Mechanism of action:

- Competitive opioid agonist (works at mu, kappa, and delta receptors)

- Displaces bound opioids from their receptors and takes their place, causing an immediate reversal of opioid-induced symptoms

Pharmacokinetics:

- Very poor oral bioavailability (5-10%); well absorbed through almost all other routes (IM, SC, IV, IO, ETT, intranasal)

- Onset of action within 1 minute for IV/ETT route, 5-6 minutes for all other routes

- Duration of action is 20-90 minutes

Indications:

- RR <12 or SaO2 <92% in a suspected opioid OD

- ***Note that decreased LOC alone is NOT an indication for naloxone; if your patient is unconscious, but breathing well, just ride it out!

Dosing:

- The main pearl here is that newer opioid formulations may require MUCH higher doses of naloxone than we are used to giving.

- Our standard starting dose of 0.4mg may often be insufficient to restore breathing.

- A paper published by Schumann and colleagues in the Journal of Clinical Toxicology (2008) looked at ED experiences with a fentanyl outbreak in Chicago between 2005-2006.

- In this paper, they found that 0.4mg of IV naloxone was a sufficient dose to restore breathing in only 15% of patients, and that the average dose of naloxone required was 3.4mg IV.

- Ten percent of patients in the study required doses of 6.0mg or higher, with the highest dose being 12mg.

This algorithm, taken from Boyer et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine (2012), is a commonly used guideline for the rapid escalation of naloxone dosing in the opioid-toxic patient:

For the patient in whom naloxone is effective, but frequent repeat doses are required to sustain breathing beyond the 20-90 minute duration of action, consider starting a naloxone infusion

Goals of Naloxone therapy:

- to restore RR >12 and O2 Sat >92%, that’s it! And remember, never titrate naloxone to try to “wake up” your patient; your goal is only to keep them breathing!

Discharge safety: This can be challenging to determine in these patients. Here are a few key considerations in your decision:

- Recall that the duration of action of naloxone is 20-90 minutes, while the duration of action of opioids can be anywhere from 1-24 hours, depending on the preparation; therefore, patients should be observed at least beyond the duration of action of naloxone prior to discharge, to ensure that they are not relapsing into apnea after the naloxone wears off. For this reason, naloxone should NEVER be used to “wake up and discharge” patients from the department.

- Understand that in the setting of overdose, the pharmacology of opioids can change dramatically, and effects may be greatly prolonged! See the chart below, taken from the Boyer study in the New England Journal of Medicine (2012). In massive overdoses or overdoses of sustained release preparations, consider longer monitoring periods.

- Consider other medical complications of opioid overdose, such as opioid-induced acute lung injury. Likelihood of this complication increases with increased severity of overdose, and is usually seen within 4 hours of ingestion.

- Take patient and social factors into account; the decision will very on a case-by-case basis!

A good general rule of thumb is as follows:

- In a patient who is asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic with an opioid overdose (i.e. not requiring naloxone)

- Monitor for 4 hours if regular/immediate release preparation

- Monitor for 12 hours if sustained release preparation

- In a patient who has a more severe OD and requires naloxone,

- Monitor for 6 hours after last dose of naloxone, or after naloxone infusion is discontinued

TAKE HOME NALOXONE KITS:

- These are not a new initiative! They have been around since the 1990s, but are awareness and use of these kits has increased significantly in the wake of the ongoing opioid crisis.

- Multiple studies (I won’t go into details here) have supported their use, finding that they increase patient understanding of overdoses and how to avoid them, and reduce overdose-related mortality, with few associated adverse events.

Who can get one?

- Legislation varies province to province, but in Ontario, anyone who is currently using opioids, is a past opioid user at risk of relapse, or a family member, friend, or other person who may be in a position to assist an opioid user, is eligible to receive a kit with no prescription, and no fee.

- Kits are available at community health centers, at many pharmacies, and in many EDs. If your ED isn’t giving these out, you should consider starting!

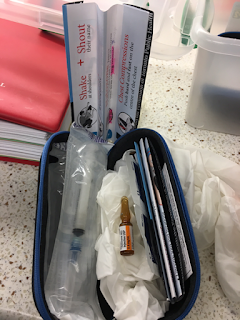

What is in one?

- A typical kit contains 2 ampules (0.4mg each) of naloxone, 2 safety-engineered syringes with 25g needles attached, 2 safe ampule-opening devices, 2 alcohol swabs, 1 pair of non-latex gloves, 1 rescue-breathing barrier, and instructions for use

Take home point:

- These kits can be life-saving. Give them out to anyone you think is at risk, or encourage your patients to get one themselves.

Managing Opioid Withdrawal

As narcotic abuse increases in Canada, the natural corollary is that we are going to see more and more narcotic withdrawal in our departments. However, this is historically something that we aren’t very good at treating in the ED. Largely, I think that this stems from a lack of knowledge and comfort with the drugs available to us for treating opioid withdrawal. Many of us prescribe only a single drug, such as clonidine or a benzodiazepine, which helps, but is usually not enough to curb all of the symptoms that come with opioid withdrawal. When treating opioid withdrawal, think about the symptoms you are trying to treat, and then use adjunct drugs to target those specific symptoms. There’s no single recipe that will work for everyone, but try different combinations of medications to see what will work for your patient. And remember that short-acting opioids are NEVER the answer to opioid withdrawal!

Here are some common symptoms seen in opioid withdrawal, and some medications that you might consider using to specifically target those symptoms:

As just one example, here is a set of orders that could be used in the ED for treatment and discharge o the opioid-withdrawing patient:

And remember that both clonidine and gabapentin are available in Canada for less than $0.25 per pill, so even for your uninsured patients, these may be good options!

LONG ACTING OPIOID-AGONIST THERAPY

Finally, if you want to make managing opioid withdrawal way easier, you could replace ALL of the above medications by getting comfortable with one simple drug: SUBOXONE!!

What is it?

- Buprenorphine + Naloxone combo pill (in a 4:1 ratio)

How does it work?

- Long-acting PARTIAL opioid agonist

- Combination with naloxone decreases abuse potential of the drug (if patient tries to inject or snort the drug, the naloxone component becomes bioactive and negates the effect)

- Partial agonist, so has a ceiling effect, therefore lower abuse and overdose potential

Why use it?

- Unlike methadone, no special license is required to prescribe it, so this is available for you to use in your ED!

- Covered under government drug plans in most provinces

- Treats ALL of the symptoms of opioid withdrawal with a single pill, so makes treatment of withdrawal easy and effective!

How should it be prescribed?

- Typically give 1-2 tabs of Buprenorphine/Naloxone (2mg/0.5mg pills) q2h in the ED until symptoms abate or max daily dose of 8mg/2mg is reached

- Then prescribe total ED dose as a single daily dose of suboxone (e.g. if a patient received 2 tablets of Suboxone 2mg/0.5mg over 4 hours in the ED before feeling well, then you would prescribe Suboxone 4mg/1mg PO q daily)

- Request daily dispensing of the drug from the pharmacy

- Only short-term prescriptions from the ED, long-term prescriptions should be managed by outpatient MDs who can follow the patient

Take-Home Points

1. The opioid crisis is real, it is here, and more is coming!

2. In managing acute opioid OD:

- If naloxone is not working, give more!

- Think about changes in the pharmacology of opioids in the setting of an OD, and use caution when deciding on discharge timing for these patients

- Recommend take-home naloxone for anyone who you think is at risk of an OD, or who might be around someone at risk of an OD!

3. In managing opioid withdrawal:

- It is essential to be good at treating this, because treating withdrawal and addiction well in the ED is the only way we are going to get past this public health crisis.

- Think about adjunct therapy, and think about suboxone!

The opioid crisis is going to be the single largest public health problem in Canada for the forseeable future, and I hope that helps you feel more prepared to handle this crisis from the ED. As front-line care providers, our engagement and competence in this topic is going to be essential to fight this battle going forwards!

References

1. Boyer, E. (2012). Management of Opioid Analgesic Overdose. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(2), pp.146-155.

2. Schumann, H., Erickson, T., Thompson, T., Zautcke, J. and Denton, J. (2008). Fentanyl epidemic in Chicago, Illinois and surrounding Cook County. Clinical Toxicology, 46(6), pp.501-506.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks